Update: This study was released in Annals of Internal Medicine on November 29, 2022 (doi: 10.7326/M22-1966).

A few weeks ago, an as-of-yet unpublished RCT (randomized clinical trial) was doing the rounds on Twitter: "Medical Masks vs N95 Respirators for COVID-19".

This Canadian multi-centre trial was posted on ClinicalTrials.gov on March 5, 2020. It had the stated goal of comparing surgical masks to N95 respirators for nurses caring for patients with respiratory illness plus fever. Nurses would be randomly assigned to wear either a surgical mask or a fit-tested N95 respirator while providing routine care to these patients. The primary outcome was lab-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, with various secondary outcomes also being tracked (absenteeism, pneumonia, ICU admission, etc.). With a 6 month follow-up period, the trial aimed to provide a timely answer to the question of whether surgical masks were no worse than N95s for caring for patients with respiratory illness.

A randomized controlled trial in which nurses will be randomized to either medical masks or N95 respirators when providing medical care to patients with COVID-19. This Canadian multi-centre randomized controlled trial will assess whether medical masks are non-inferior to N95 respirators when nurses provide care involving non-aerosol generating procedures. Nurses will be randomized to either use of a medical mask or to a fit-tested N95 respirator when providing care for patients with febrile respiratory illness. The primary outcome is laboratory confirmed COVID-19 among nurse participants.

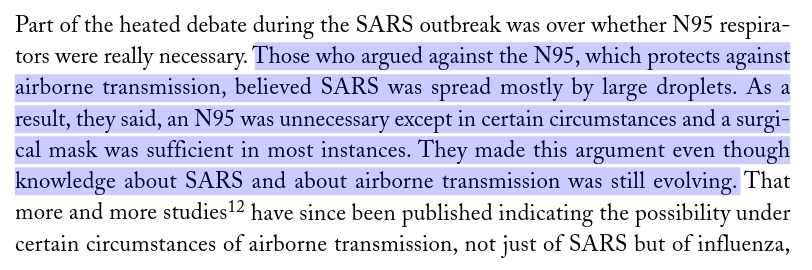

Although this trial may seem anachronistic in light of the past two and a half years (for much of this time, healthcare workers have been masked for all routine care), it's important to note that it was conceived of in February of 2020 (or earlier). Think back to that time: a lot of Westerners (including me) considered masking a cultural curiosity rather than a rational response to a reoccurring threat of epidemic respiratory disease. The public health messaging on masks was all wrong at the beginning. We were happy to ignore the warnings of aerosol scientists, not to mention Ontario's very own SARS Commission. Own up and move on.

In May of 2020, this trial received $624,953 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) as part of a rapid research funding opportunity for pandemic-related health system interventions.

According to the clinical trial registration, the trial has a start date of April 1, 2020, an estimated primary completion date (i.e., the date data collection finishes for the primary outcome) of February 1, 2021 and a final study completion date of April 1, 2021.

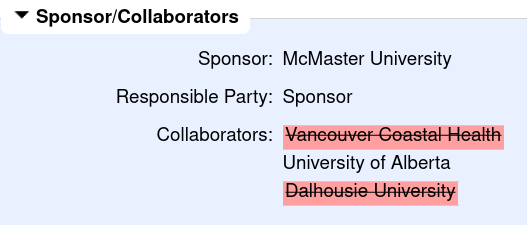

And yet here we are in August 2022, 16 months after the estimated final completion date, and...nothing. ClinicalTrials.gov lists the current recruitment status for the trial as "unknown". The last update posted was on February 9, 2021. It struck out two of the three institutions previously listed as collaborators, leaving only the University of Alberta.

The confusion surrounding this publicly funded clinical trial got me thinking about the larger issue of clinical trial transparency. Clinical trials are unbelievably expensive, but despite this a large fraction are never published. Not only does this constitute a massive and avoidable waste of resources, but it is frequently the "negative" studies (studies that fail to detect an effect of the intervention) that go unpublished. This so-called publication bias has distorted the medical literature for decades, misleading us regarding the effectiveness of interventions of all kinds.

Reporting the results from clinical trials has been getting better, although mainly due to regulations that force mandatory reporting, like those in the UK and US (the US FDA has the power to levy large fines for failure to report clinical trial results in a timely manner, but it has thus far declined to do so). Trial registries like ClinicalTrials.gov provide a venue where trial results may (or in some cases, must) be reported, independent of a publication in an academic journal.

It turns out that CIHR, the funder of the trial at the heart of this post, is also getting in on the clinical trial transparency game. According to new regulations, for all trials funded on or after January 1, 2022, summary results must be available within 12 months of the end of data collection for the primary outcome (i.e., the primary completion date mentioned earlier). Failure to comply means becoming ineligible for future CIHR funding. Going by the publicly announced timeline, with the primary completion date of February 1, 2021, this trial would be in violation of reporting requirements had it been funded in 2022 instead of 2020.

Looking at the available information, it wasn't clear to me if the trial ever did reach primary completion. In fact, it wasn't really clear if the trial ever got off the ground at all. Were any nurses recruited? Were any data collected? Was their trial protocol overridden by changing infection control protocols (e.g., mandating that healthcare workers be masked at all times)? What happened to the funding from CIHR? I had no answers to any of these questions.

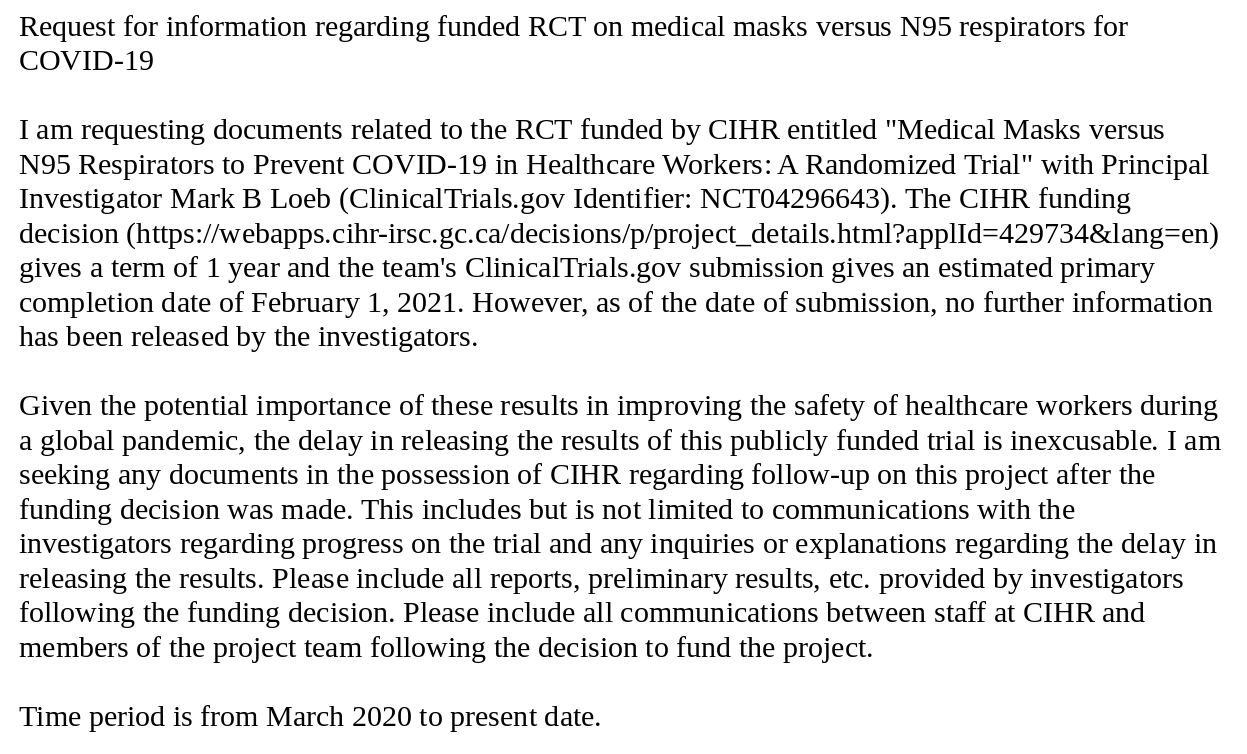

So I paid the $5 to submit an Access to Information Request to CIHR. You can see the text of the request below. In short, I was looking for any information that would give a clue as to the status of the trial.

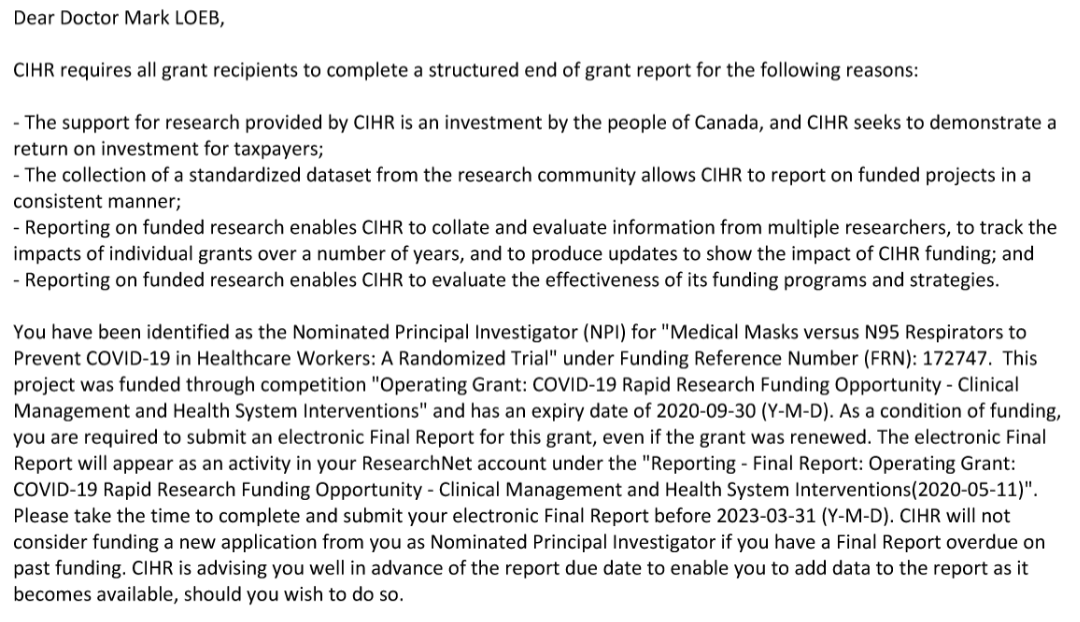

Two weeks after CIHR received the request, I got a response. It consisted of a single email from CIHR staff to the primary investigator of the trial, explaining that the final report for the trial must be submitted by March 31, 2023.

As far as I know, these final reports are not public.

So it seems there is not much we can do at this point except wait.

A final note: this should go without saying, but please do not harass any of the people involved in this trial. If they wanted to release more information about it, they would have already.

If you learned something from this post, please consider subscribing using the button at the bottom of the page.